Foreign correspondent and bureau chief for IHT, Knight Ridder, New York Times, etc. Author of the new PTSD novel, Off the X, Mark McDonald (K73) returned to Kalamazoo this winter and spring to teach two courses in Journalism.

Two interview-based assignments that I used in the Winter and Spring terms seemed particularly successful with the students, and I think they could work across a range of departments, subjects and courses at K. I first used them in the journalism and politics seminars that I taught at the University of Michigan.

Example One:

As part of a Reading the World/Genre class called “Media Literacy,” we read a snappy, timely new book by Bob Garfield, who co-hosts a weekend media/politics show that’s heard on NPR. (In the world of mainstream journalism, he’s kind of a minor celebrity.) We read and discussed a chapter or two each week and finished by the seventh week. I had called Bob earlier and he agreed to Zoom-speak with us in Week 8.

Each student sent in a couple questions beforehand, which I edited down to a dozen or so, and Bob joined us for 90 minutes one afternoon. With 30 students jammed onto Zoom, having a free-flowing, back-and-forth discussion was a little unwieldy, but not too bad. All the scripted questions got asked/answered, we had time for several impromptu ones, and Bob delivered a rousing outro that was both a challenge to the students and a call to civic action.

Most of the students were kind of stunned that we were actually talking to the person who wrote the book we had just read. They didn’t buy into all of his arguments and positions, to be sure, but that was an instructive part of the experience, too.

Now, I realize that any number of professors deploy guest lecturers when we’re on campus, sure, but online classes make Zoom appearances by luminaries and superstars all the easier now. Hey, they’re just sitting around at home, too. Aren’t they dying to talk to someone, especially student-fans at our hot little liberal-arts school? Zooming also precludes the need for a guests’ travel costs, sizable obligations of time, and honoraria. (Marin Heinritz freed up some ENGL money that allowed me to send some K-branded gifts to Garfield as a thank-you, and Debbie Thompson pulled the items for me. Sixty bucks, all in.)

Example Two:

I used another somewhat unusual assignment in both the RTW class and my Shared Passages seminar titled “Combat, Conflict and International News.”

In the sophomore seminar, each student was required to interview a working journalist, preferably someone with international news experience. (Diplomats, aid workers and combat veterans were OK, too.) I encouraged the students to think big. Google people. Give it a shot. Look on Facebook, Twitter, university and NGO websites, Instagram, whitepages.com. Cast a wide net, I told them. Aim high. Be resourceful.

When I debriefed them afterward, most students said they had been wholly intimidated by the assignment. They were sure they wouldn’t be able to identify anybody, or find their contact details, or get folks to agree to talk. “How do I interview someone? Do I record the thing, or take notes? How many questions? What does off-the-record mean? Is a conversation an interview? What happens if they bail on me? Why would they talk to ME?”

Were they stressed? Daunted? Uncertain? Maybe a little scared? A little angry? Yep, all of that.

I helped about half the students with names of people I know in the journalism business; the other half found interviewees entirely on their own. Nobody failed to find somebody, although several students did have to resort to Plans B, C or F. (Which was part of the assignment, too, of course. Welcome to the life of a working reporter.) Some students panicked a little, but they all persevered. In the end I think they quite surprised themselves — and were proud of what they saw as a real accomplishment.

And some of their “gets” were stunning. One sophomore found and interviewed the courtroom sketch artist assigned to the Guantánamo Bay prison tribunals. (She even got permission to use several original sketches of the detainees in her presentation; the sketches came with approval stickers from Defense Department censors.) Two students landed superstar writers from The New Yorker, and a dozen or so reached and interviewed New York Times and Washington Post reporters, including a handful of Pulitzer winners. Several interviewed combat photographers. One student got a long interview with Linda Greenhouse, now at Yale Law, perhaps the country’s foremost expert on the Supreme Court. Another found a female combat officer who’s a policy analyst at a big D.C. think tank. Another interviewed a Houston-based reporter who has been covering femicide in Mexico, an issue we examined in class. So many examples like these. Really remarkable.

Within the first two weeks of the seminars, each student also had selected a book from a list of 30 relevant titles that I provided. (One book per student, no overlaps. Most chose books on their own; a few needed a little guidance. They were to read the book throughout the term and do a substantial critical essay on it by Week 9.) Anyway, for their interview assignment, a dozen or so students tracked down the authors of their books. They were clearly thrilled when they found the writers freely exchanging thoughts and ideas with them — mere college students!

I left the scope and presentations of the interview projects up to each student — written Q-and-A transcription, recorded Zoom interview, PowerPoint, audio file with written text, whatever. One student did a manga-like presentation on Acrobat. One wrote an epic poem. Another made a short documentary film.

Predictably, perhaps, most students wanted to know beforehand exactly what I wanted, what questions to ask, how long the interview should be, how many pages of transcript, what format I preferred. I refused to answer these questions. The students were not comfortable with this AT ALL, and they gave me a good bit of heat about it. They complained that “You’re not being clear.” They wanted to succeed, of course, and not having specific metrics and parameters was new territory. Their stress was almost palpable. Still, I left them to their own devices — and they all succeeded. In splendid fashion.

The Bob Garfield appearance and the interview assignment showed the students that “unthinkable “things are indeed quite achievable. Also, feeling intimidated and uncertain needn’t be paralyzing. You’re 20 years old but you CAN operate and succeed on your own initiative in the wider world. (I suspect this kind of lesson is especially helpful for second-years who have yet to study abroad.) Famous authors, scholars, soldiers, journalists, civic leaders — they’re within your reach. They were 20 once, too.

To sum up, I think this kind of assignment could be useful in any number of courses at the College. And I will apologize in advance for what will likely sound like a rant, but we can easily and obliquely teach the students to think big and dream bigger by using unusual interview assignments or Zoom visits.

Like visits from working artists, musicians, dancers, theater/film folk. Historians, scientists, judges, journalists, engineers, novelists. Call up the U.S. poet laureate, or a former one. Try to land the head of design at Tesla, Ford or Shinola. Invite the winner of a Fields Medal to speak to a Math class. Get a Nobel laureate in economics like my friend Joe Stiglitz or Esther Duflo, who works in poverty alleviation. Zoom-interview an archeologist on site at a dig somewhere — Italy, China, Greece, Mexico.

Get the author of your class textbook to Zoom with you for an hour. We have supremely accomplished alumni in countless disciplines who would love to help out, too. Farmers and entrepreneurs. Interview a former soldier from the My Lai massacre, like the combat photographer who was there that day and blew the scandal open. (He’s 80 now and lives in Cleveland, by the way.) Call up the heads of Black Lives Matter, Planned Parenthood, the ACLU, the NRA. So many of these folks will happily and graciously talk to students or classes. We just have to ask.

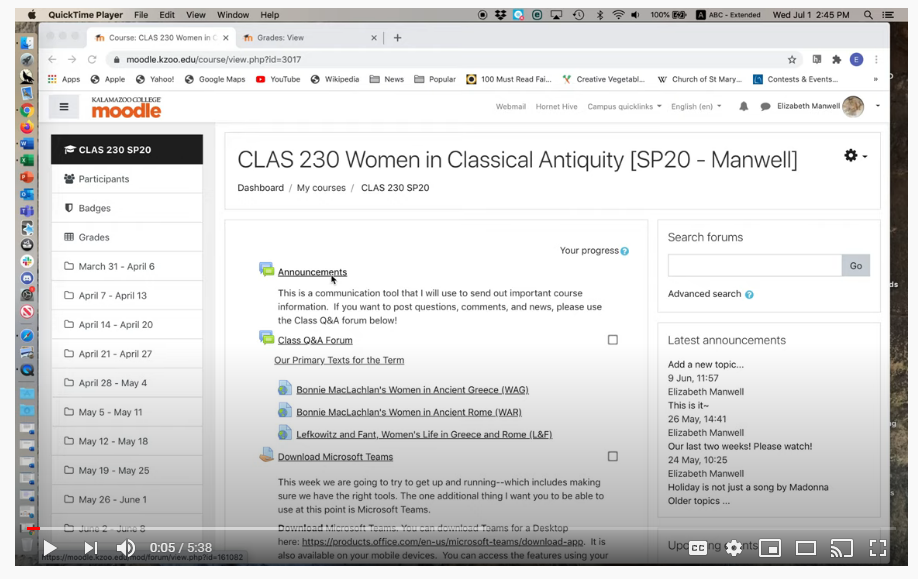

) on the main page of the course includes the settings for the class, while elements like Files, Forums, and others have their own “Edit” options to access the settings. Don’t hesitate to ask if you have a question about what a setting does! Also, Moodle’s question mark icons (

) on the main page of the course includes the settings for the class, while elements like Files, Forums, and others have their own “Edit” options to access the settings. Don’t hesitate to ask if you have a question about what a setting does! Also, Moodle’s question mark icons (