I’ve just finished what turned out to be an emotional week reading all the course evaluations from the fall term and soaking up those powerful bite-sized reminders of the difficult times everybody has been through. I saw reflected in those comments the typical mix of contradictory classroom frustrations: too much/little workload, too much/little groupwork, too much/little class discussion. On top and Interleaved with those were reports of students’ and instructors’ issues with the online course delivery media: internet connectivity and limitations of various software platforms. I read students’ reports of life frustrations and worries, for which we once believed the K bubble offered a degree of protection, growing beyond any assistance or support our tentative online classroom communities could ever provide.

Below I’ve summarized what I saw in student course evaluations around five themes:

- Comparison with previous terms: response rate and instructor rating

- A lot of students report experiences of transformational learning, without regard to the course delivery medium

- Course Structure and Instructor Feedback

- Students’ sense of vulnerability in the pandemic world

- Different students experience groupwork differently

1. How did course evaluations during the extraordinary online fall term compare with previous years?

Response Rate

In the paper-and-pencil era of course evaluations, response rates to the the in-class surveys were typically around 90% — dependent simply on the proportion of students in attendance on evaluation day. Winter 2020 was the first term of online course evaluations using the SmartEvals platform. Even with the disruptions of the rapidly emerging pandemic shutdowns on Thursday and Friday of tenth week and the winter final exam period in March 2020, the response rate was 85%. With the expectation that these online evaluations would be completed in the classroom during class time, there was every reason to expect response rates similar to the paper-and-pencil days.

Then spring happened. We all remember the widespread difficulties experienced by both students and instructors. Alarming numbers of students faded away over the course of that term, during what we’ve come to call “contingency online instruction.” The wave of protests and civil unrest in late May and early June drained whatever remained of class engagement at the end of that term. Those factors can be easily seen in the very low 35% response rate to online course evaluations for spring 2020.

For fall 2020, the student response rate to online course evaluations at K was 65%. That’s good news compared to the spring term, but far lower than we’ve come to expect. In the comparisons below, it’s important to keep that missing one-third of student voices in mind. I recently reached out to instructors whose students responded at high rates, and have compiled a blog post about practices they report using to encourage student engagement with the online course evaluation.

Instructor Ratings

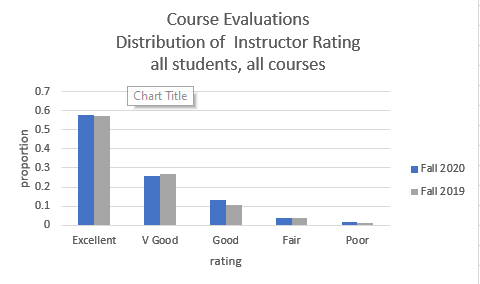

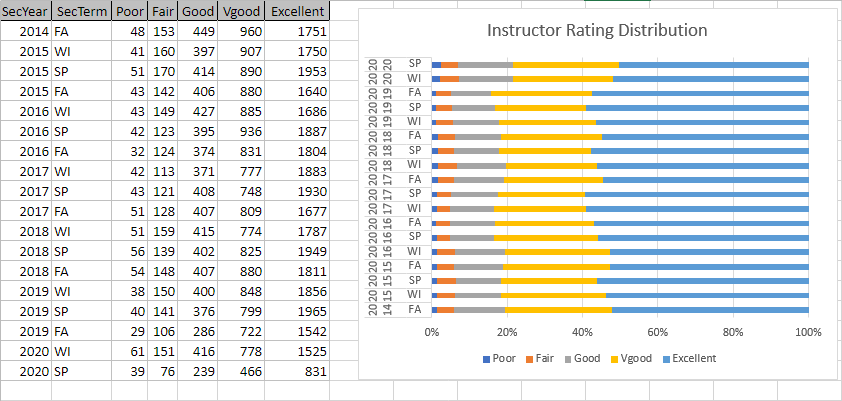

In reading survey results, there is always a concern about over-representation among students who have strong feelings to express, both positive and negative. This concern is only heightened with less than universal response. Following up on questions from several instructors about that concern, I considered Instructor Rating scores from the fall. Averages don’t shed light on the question of bias toward stronger opinions. For that purpose a closer look at proportions of responses at each rating level can illustrate the issue and aid in comparisons. The chart below shows distributions of Instructor Rating responses for Fall 2020 compared with Fall 2019. The distribution of ratings is remarkably similar between these years. I think this gives reassurance about possible negative effects of online course delivery in students’ rating of their instructions.

The proportions at each level aren’t exactly the same between these two years, but the differences are well within the year-to-year variation over the past half-dozen years, illustrated in the next figure.

2. In this online environment, Students Report Familiar Experiences of Joy in Learning

As I read evaluations course by course and department by department, an unmistakable trend emerged that has left me feeling profoundly grateful to the K faculty and optimistic about the days ahead: so, so many students reported on their experiences of transformational learning in courses this fall, in many cases without even mentioning the online delivery medium. For instructors, it’s all too easy to fall into a kind of despair, questioning the possibility of profound student learning outcomes without the traditional personal touch that has characterized the K student experience. Here are a few quotes from student comments that illustrate the learning experiences students experienced this fall:

This has been an incredible class, and I so appreciated all of the intersectionality and different topics we covered. I learned so much, and this class definitely reignited my passion for the subject!

…was phenomenal about reading where students were at, what kind of feedback they needed, and where they were struggling.”

I have been waiting to take [this course] since I started college, and the class did not disappoint. I found myself genuinely wanting to read and go to class due to the content, as well as the structure of class.

I totally understand why everyone wants to take this class before they leave K.

… is the kind of instructor that I came to Kalamazoo College to learn from.

Je me sens plus confiant en mon francais grace a ce cours

I feel this is an excellent first year class as it has challenging academic readings daily and introduces students to academic thinking and writing. I feel I am better suited for college-level work because of this class.“

this class encouraged and was centered around thinking of things from different perspectives and with your imagination, and [the instructor] always prompted us to think outside of the box and analyze things from a different point of view

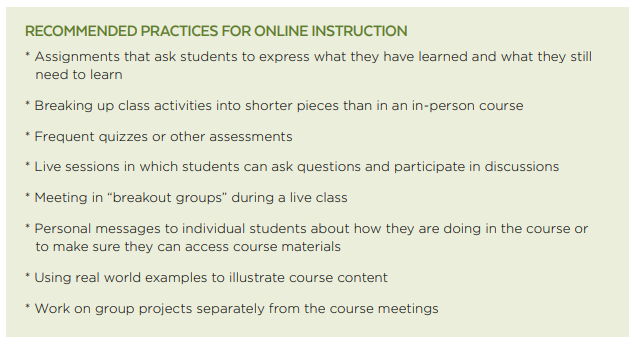

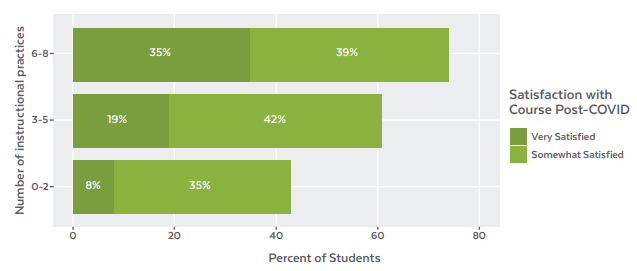

3. Students report high levels of satisfaction with courses that provide clear structure and timely feedback

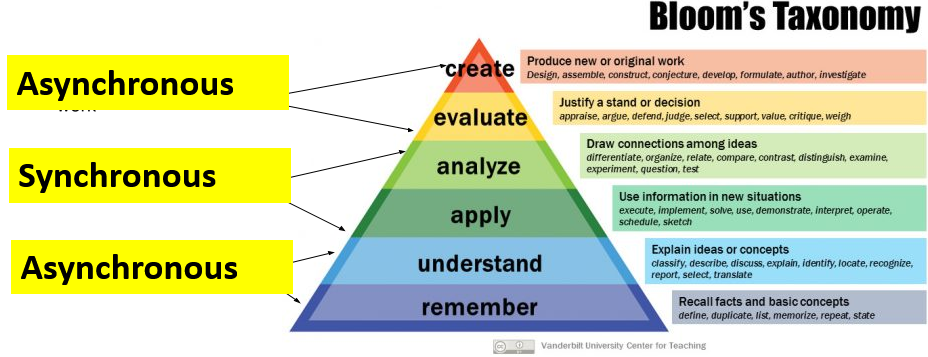

Without the in-person classroom opportunities for instructors to gauge where students are in their progress through the course and clear up misunderstandings, students reported confusion and mistaken negative assumptions about class structure that lead to irreversible dissatisfaction with courses. Only rarely did I read student accounts of courses that were able to overcome confusion about assignments, due-dates and missing grades. In those cases, the balancing factor was a strong relationship with the instructor and classmates through extraordinarily effective synchronous class meetings.

In the online environment, where the difficulties in establishing nuanced personal communication are widely acknowledged, clear structures and well-established patterns of frequent timely feedback were positively brought forward by students in reporting course satisfaction. And importantly the lack of those factors was the most frequently cited reason for course dissatisfaction.

4. Students’ overall satisfaction in courses this fall often boiled down to the perceived level of support and understanding of pandemic-related factors

I don’t have a quantitative measure of this phenomenon, but my reading of their survey comments convinces me that students this fall felt very vulnerable in the face of the pressures and anxieties of the pandemic world, and in many cases this formed the background for their nascent interaction with their instructors. In reporting their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with courses, students in many cases — far more frequently than I can ever remember from my work with student course evaluations in the past — tied their experience of the course with their perception that the instructor did (or sadly did not) truly care about them or what they were going through outside of schoolwork. Those students that gave more details in this regard pointed to flexibility with due dates, instructor responsiveness to student feedback about course structure and workload, and instructors reaching out with expressions of support, care and kind concern.

5. Students Loved/Hated Groupwork this term

A frequently reported feature of high student satisfaction courses this term was the effective use of breakout discussions and group work. Remarkably, the opposite is also true: many students reported low satisfaction with courses due to their experience in smaller group structures. In several cases, students in the same course experienced this groupwork as the make (or break) feature.

Several students acknowledged their negative experiences stemmed from the make-up of the groups: the familiar reports “I did all the work, nobody else did anything” were amplified by perceptions of disengagement in the video meeting setting (“cameras off”, “stays muted”, etc). Likewise, a number of students reported positive work together and friend-making from groups.

I didn’t gain any new solutions to this problem from what I read in the course evaluations, but it does strike me that because the breakout discussion is such an important part of the online class meeting, it will be important for us as instructors to give this issue some careful thought, with special attention to how group memberships are assigned and monitored for signs of distress. I’d love to hear your ideas about this in a #KTeachDev2020 post!

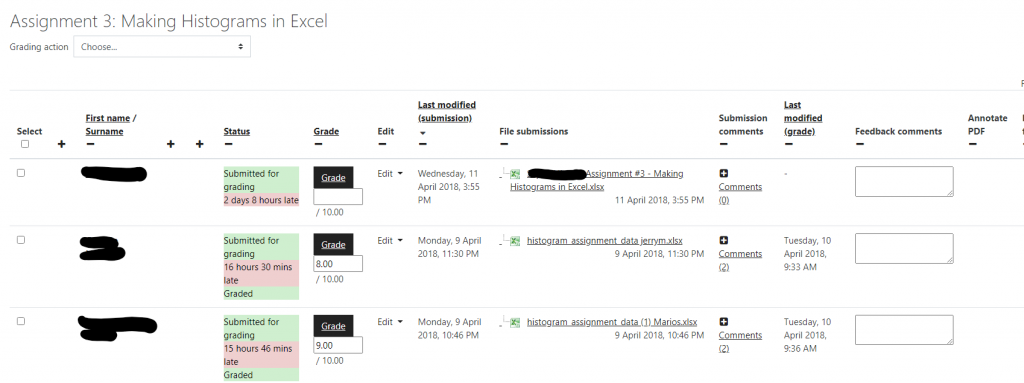

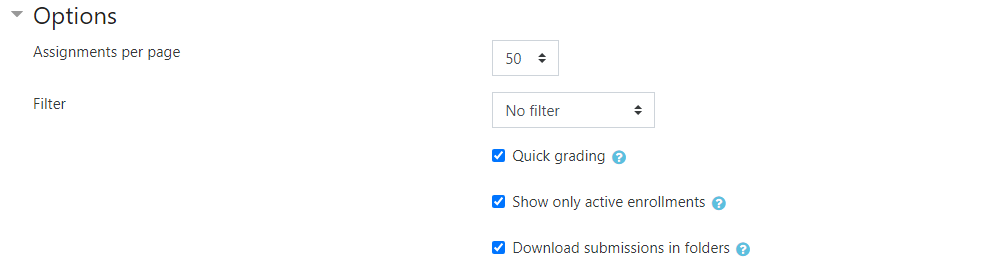

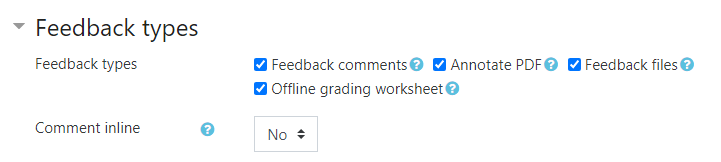

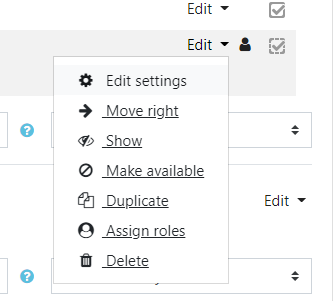

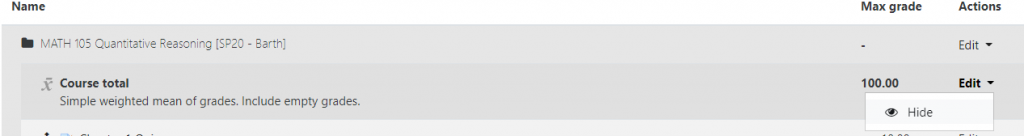

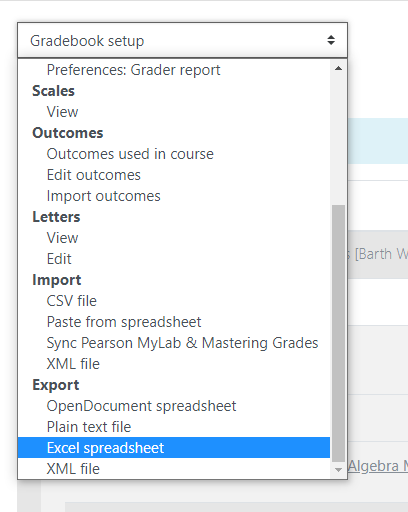

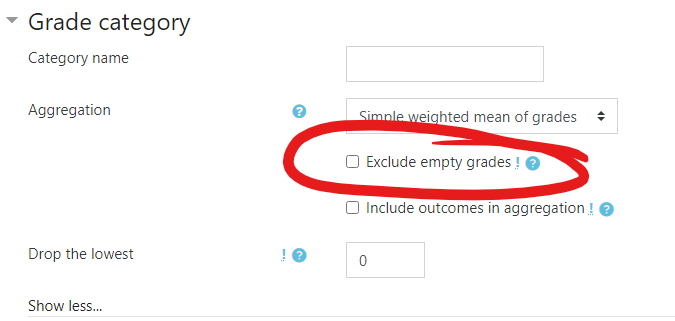

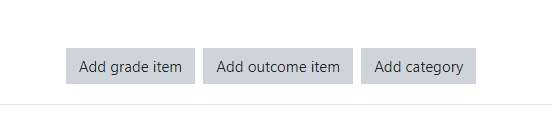

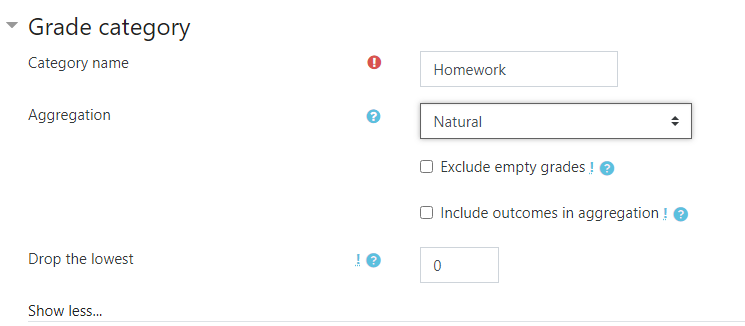

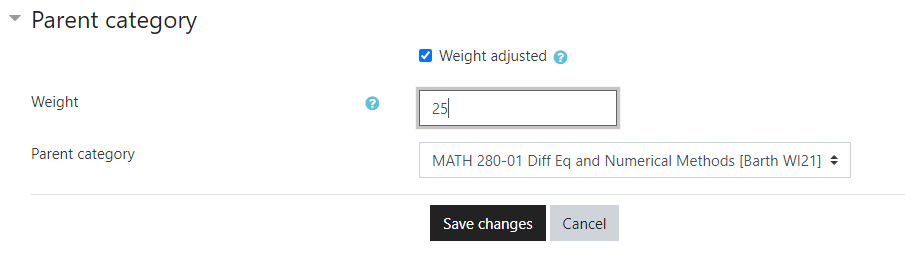

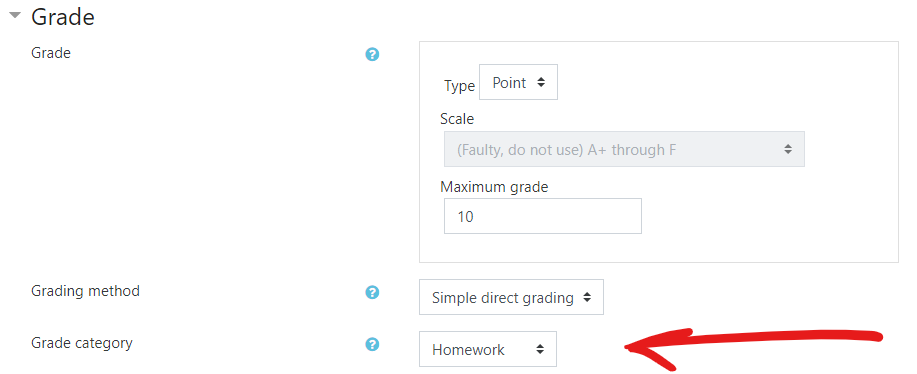

) on the main page of the course includes the settings for the class, while elements like Files, Forums, and others have their own “Edit” options to access the settings. Don’t hesitate to ask if you have a question about what a setting does! Also, Moodle’s question mark icons (

) on the main page of the course includes the settings for the class, while elements like Files, Forums, and others have their own “Edit” options to access the settings. Don’t hesitate to ask if you have a question about what a setting does! Also, Moodle’s question mark icons (