The Moodle web interface allows easy categorization of the questions, but that method will take time if you want to create a big test bank since it requires multi-step navigation via on-screen buttons to write each question.

Here I’ll show straightforward ways to construct and import questions to Moodle and create a question bank.

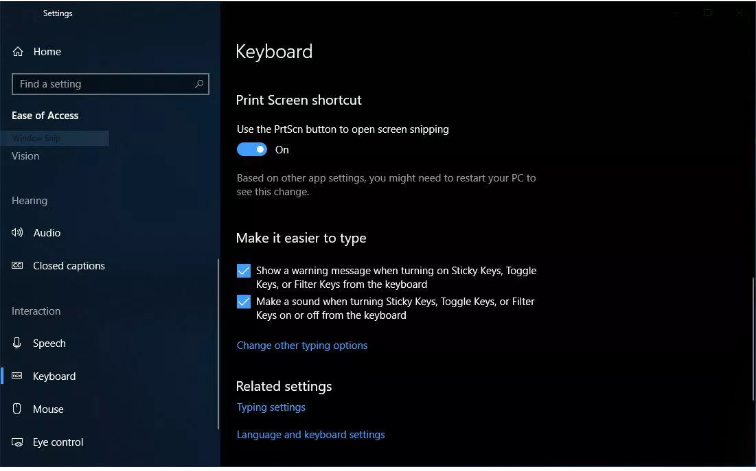

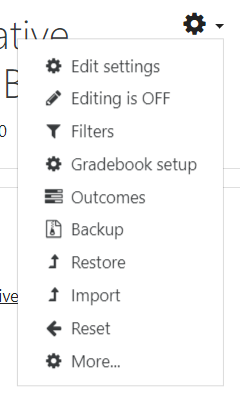

Once you’re logged into the course page on Moodle, click on the gear symbol on the top right window, then choose More…

Scroll down to the bottom of the page and you’ll see Question Bank

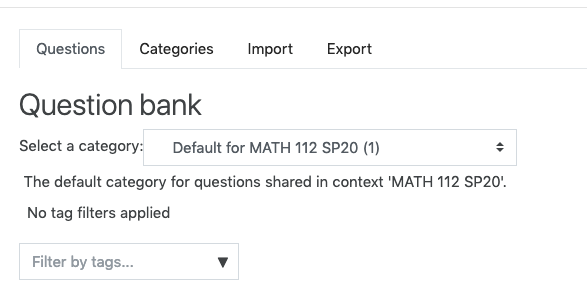

If you’d like to create a new question in a particular category, you should choose the destination category from the drop down list before hitting Create a new question button. From here, there will be on-screen navigation to help you choose the question types and write the questions.

Importing questions in the Aiken Format

The Aiken Format works best for multiple choice questions. Many multiple multiple choice questions can be written in the same text file then imported to Moodle. For that reason, this method saves a lot of time because you don’t have to go through multiple steps to write an individual questions like in Moodle Web. An example of Aiken format is:

Question text

A. Choice 1

B. Choice 2

C. Choice 3

ANSWER: DSome things to note:

- ‘ANSWER’ must be all capitalized, followed by : and a space. Otherwise, Moodle will give you an error during the import.

- .Each answer choice must start with a single uppercase letter, followed by a period (.) or parenthesis ), then a space.

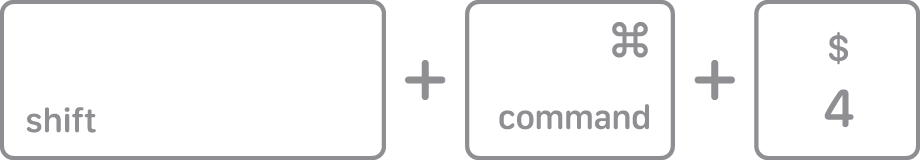

- The file has to be saved as plain text (.txt)

- The Aiken format supports Latex Math symbols. You can use ∖( and ∖) or the double-dollars signs $$ $$ for Latex math mode. Commonly used math symbols in Moodle are detailed in Rick’s previous post.

- The Aiken format only supports multiple choice questions so if you want to add a variety of the question types (short answer, calculated, multi-parts quetions, etc. ), this format might not be for you.

- It seems that graphics or any kind of text formatting can only be added manually after the questions are imported to Moodle. In Windows, the built-in text editor NotePad provides the plain-text format. In macOS, the TextEdit program is found in the Utilities folder in Applications.

Once you have created a text file with questions in the Aiken format, select “import” from the Question Bank menu in moodle and navigate to the text file.

Creating question banks in Google Sheets

(QB)2 is a user-friendly add-on to help educators write and manage question bank directly in Google Sheets. It is also a great tool to bring your current question bank online.

You can install the needed extenstion to Google Sheets by selecting Add-ons and searching for (QB)2

After installing and activating the add-on in Google Sheets, you are ready to begin creating quiz questions. This 6-minute video shows you how.

More help on (QB)2 is available in this video from the package developer.