Anne Marie Butler — Art History

Restructuring & rethinking grading, including: How do we measure engagement?

- I have removed the engagement and attendance policies from my syllabi. One of the major grading areas is group work, and student provide peer and self-evaluations on the group work. In the attendance and engagement areas of the syllabus I note that this is not a grading area, but that frequently missed classes may impact group work and that peer evaluations may reflect that.

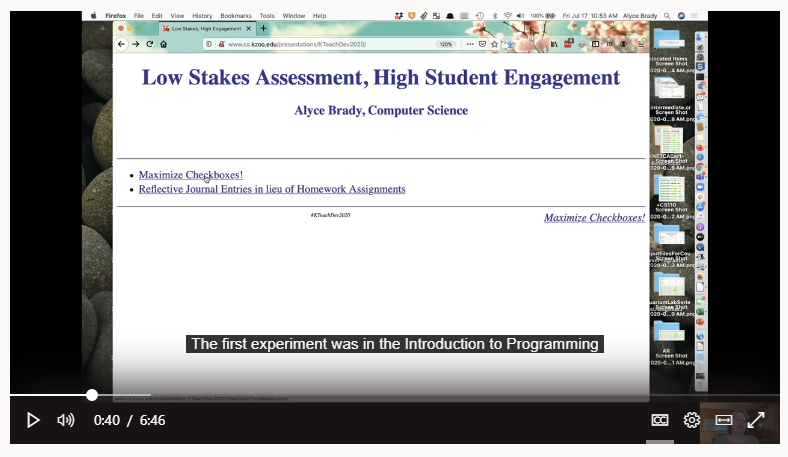

Alyce Brady — Computer Science

Along the same lines as Anne Marie, I changed my “Attendance and Participation” section in my syllabus to “Participation and Staying on Track.” The specific language is now:

This course covers a breadth of topics, with many small activities that build on one another. It is very important to remain actively engaged in the course on a daily basis in order to stay on track.

Given the hybrid nature of instruction this quarter and the constraints imposed by social distancing, students will be divided into small lab groups. Participation will consist of attending at least two synchronous class meetings with your lab group each week, whether in the classroom or online. Your lab group will also have a dedicated “space” online in the course Teams site where you can work individually or together, ask each other questions, and meet with the instructor.

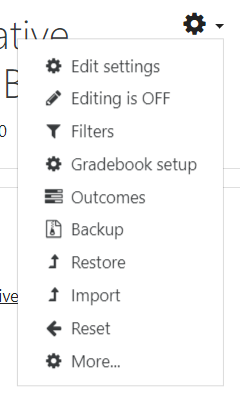

Here are some other changes I’ve made in my classes to reflect my thinking about grading practices. I’ve also posted a longer vlog piece on this topic.

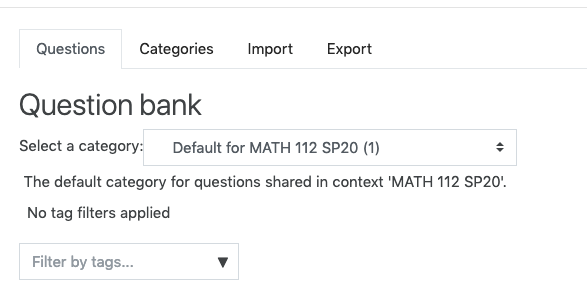

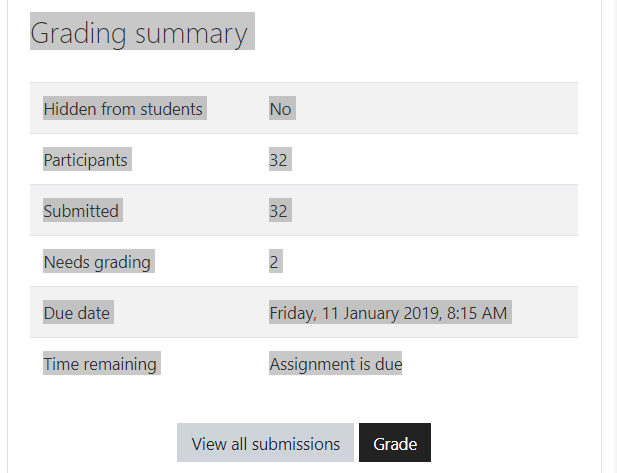

- Turning rubrics that awarded points for required criteria into ones that awarded checkmarks, dramatically reducing the number of points per assignment. This approach is essentially a very mild form of gamification. (It is also somewhat similar to specifications grading.)

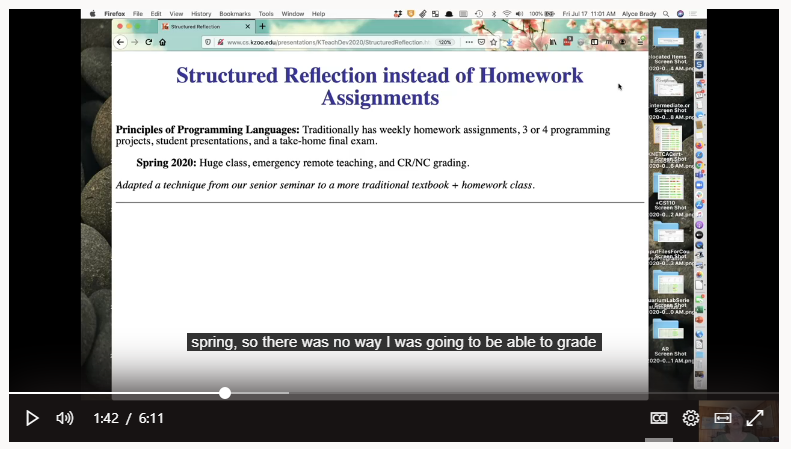

- Replacing traditional homework assignments with structured reflection assignments. My original motivation was to reduce grading time, since the class was significantly over-enrolled. I feared that some content learning would be lost, but found that the weekly writings encouraged students to develop and articulate greater depth and integration than the older homework assignments.

Rick Barth — Mathematics

I’ve been thinking about assessment in the online era from two points of view: equity and honesty. These have led me to a single set of conclusions and recommendations. I’ve come to believe that traditional assessment methods — to the degree that they are designed to reward generic skills rather than individual student experiences — dehumanize further the online learning experience, exacerbate existing inequities that have been made worse by the pandemic, and provide every incentive for students to seek ready-made generic responses to represent as their own. My aspiration in my own courses is to include more assessment methods designed to gauge students’ individual learning and progress over time, and to be as valuable for me in adjusting my teaching as they are in helping me determine student performance. I explore my ideas about this in a longer blog piece.

Josh Moon — Instructional Technology Specialist

I’ve become increasingly persuaded that fixation on grades can be a distraction to learning and productive engagement. Worse, grades function as a tool to disproportionately punish students who are not adept at navigating the college environment. They can be the #1 carrot/stick on a campus, the celestial body whose gravity pulls in time, resources, and attention. I’ve written more about this in a piece at my blog.