In this video blog I share my thoughts on how I’ll use digital whiteboarding in my class this fall. I teach organic chemistry, a discipline that is rooted in drawing chemical structures — lots of pictures! To help students understand this discipline, its helpful to do this work together. I plan to run my class in a semi-synchronous fashion, interacting with students in real time using Google Jamboard.

Category: Contributed

Connecting at a Distance — Bruce Mills

As the weeks progressed and things got increasingly difficult, I appreciate[d] Dr. Mills giving us the space to speak/write if we needed to and step away if we had to. I don[‘]t think this online transition was perfect, but I think Dr. Mills was consistently thinking about us as people and then as students, and I think that is why I got as much from this class as I did

Even though this class was also asynchronous, I felt a connection to the professor and my classmates that seemed to have been the product of these [weekly MS Team] discussions. It was something I looked forward to every week, because I always left that call feeling as though a weight had been lifted off of my shoulders. In times when (emotionally and physically) close contact is nearly extinct, being able to connect with others through serious and relevant texts (and also just have a safe space to discuss personal issues and beliefs) was relieving

I would like to pretend that every student left my spring courses with these same feelings. I am not so naïve. Still, I call them out as both an individual and communal affirmation. In departmental conversations (and across campus) with colleagues, I heard folks imagining and sharing humane and equitable practices —for students and ourselves. We centered on access (to readings and technology), on transparency, and thus on removing barriers that impede learning. Amid this crisis, I was reminded of an essential core to teaching: caring is content.

Let me also offer one final note before the resource link below. As a teacher, I see student motivation and learning as linked to feeling “named” or “seen.” It is about keeping an eye on connecting. Certainly, and this was no small task in the transition to online instruction, the strategies and technologies had to change for this connecting with students. However, the central arc of my pedagogy did not. This centering objective gave me confidence in choosing to select fewer chapters from Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider and, in the case of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, to read only the Prologue, Chapter One, and the Epilogue. It also led me to check in frequently with students and, out of these conversations, standardize days/times for weekly information emails, for weekly Moodle postings, and for group discussions (4-6 people) on Teams.

Alongside this effort to provide a reliable schedule, I instituted a philosophy and practice of reasonable flexibility. The linked article in The Chronicle of Higher Education (“5 Ways to Connect with Online Students”) offers a useful summary of things that mirror my own efforts during the spring.

Note: these suggestions point to additional workload in some areas and, as a result, the need to spend less time in others.

Bruce Mills

Department of English

Online College: General Advice from My Own Experiences — Lars Enden

As someone with a fair amount of experience with teaching in online environments, I’ve been asking myself lately what kind of advice I would like to give to you, my fellow colleagues, that would be both useful, general, and different from what you’ve probably already heard. I have taught over 40 online classes in my career, and I feel like I have learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t work in an online classroom, but I have had a hard time figuring out exactly what to say to distill that experience into something directly pertinent to professors who have been hurled headlong—against their will—into the world of online teaching. What can I say to you that might be of some help? Well, as a philosopher, I tend to think about these things in a theoretical way. So, I humbly submit my answer in the form of a theory.

The Problem of Online College: A Theory

The problem of online college is simply that when students take online classes, there is no college. If you think about the traditional college experience from the viewpoint of a student, it has a certain “feel.” The student wakes up in a dorm (or at least in housing near the campus); the student eats in the dining hall with other college students; and the student goes to classes at a regularly scheduled time. In other words, there is a college routine—a college culture—a sense of being a part of a college. All of that tends to get lost in the online environment; there is no college, there are only classes. In the world of online education, the typical student wakes up in their house with their parents, siblings, etc.; the student eats in their dining room or on their couch with those same parents, siblings, etc.; and the student doesn’t really go to classes at all. In short, the experience is domestic rather than collegiate.

With this problem in mind, I want to suggest that the best online classes are the ones that have been developed—from the beginning—to feel like college. In my experience, the professors that are the most successful in the online environment are those that put thought and effort into designing their classes to feel like college classes rather than merely classes.

I think that this problem manifests itself in a number of different ways, and I would like to share some ideas about three different manifestations of the problem that I think should be addressed while designing an online course.

The first manifestation of the problem of online college that I want to address is the issue of student motivation. Even students who are ordinarily engaged and excited about their classes can often feel unmotivated when taking online classes. One of the main reasons for this, I suggest, is the lack of a campus, which tends to diminish the feeling of being in college. The gravitas of the campus classroom is replaced by the mundanity of a laptop or a smartphone. From my experience, the best way to combat this problem is to maintain a routine that keeps students on task. I have found that frequent small assignments are great for helping to develop and maintain a routine that mimics the college experience of going to classes regularly. I suggest having something due at least every other day. Make it something educational, small, and, most importantly, required. This not only helps to establish a routine, but it also helps the professor get an early feel for students who are disengaged or struggling. I also suggest being rigid with due dates. I understand the impulse to be flexible with due dates in an online class, but my experience suggests that such a policy just tends to further diminish the feeling of being in college among the students. When professors are firm with due dates, it feels more like college to the students, and they are more likely to take it seriously. For example, the Logic and Reasoning class that I taught in the Spring included homework assignments for every class meeting day (3 times per week). So, students had to keep constantly on top of this work, and I only allowed them to get lower than 70% on two of the assignments and still be able to pass the class. That might sound like a harsh grading criterion, but they all knew that there were consequences for slacking off, which helped to keep them on track and engaged. Of course, students sometimes have issues getting their work done on time for various reasons: I am not suggesting that we should just say “tough luck” to them, but I think that professors who are officially flexible with due dates in the online environment tend to send the message to their students that their classes are just classes rather than that they are college classes.

The second manifestation of the problem of online college that I want to address is the issue of the feedback loop. By feedback, I don’t just mean the comments that we give on individual student work; that clearly still exists in the online environment. The feedback loop that is missing is the one that exists in the classroom. Students are used to constant feedback in the college campus environment. In a traditional classroom, there is continuous student-teacher and student-student interaction. The feedback loop is almost instantaneous in this environment, and the amount of information exchanged is massive. Even the look on a single student’s face can tell you a lot about their level of understanding, and, on the flip side, the teacher’s tone of voice or body language can convey a lot of information about a topic to the students. In an online class, the feedback loop is much, much, much, slower, especially in classes where the feedback loop is done almost entirely in writing. From my experience, a good way to combat this issue is to get as much face-to-face time with the students as possible. Engaging in a live feedback loop is best, but even recorded videos (from both student and teacher) can go a long way toward developing a sense of engagement that is often missing in online classrooms. Obviously, it is not always practical to hold live meetings, but if you can, I strongly encourage you to try it. This past Spring, I held my sophomore seminar on the Philosophy of Religion as a live, synchronous class, and the students could not stop thanking me for it! However, this was a relatively small class of about 13 students, and none of those students had time-zone issues or major connectivity issues. So, it was a blessing to be able to hold the class in this manner for the entire term. As a counterpoint, my other class in the Spring (Logic and Reasoning) had about 32 registered students. For that class, required live meetings were impractical, but I still wanted a good amount of face-to-face interaction. So, I decided to hold live lectures, but I also recorded them so that those who could not or did not want to attend could view them later. The in-person feedback loop was still there, but in a more limited way. Even if live meetings are out, I still strongly encourage all online professors to put in some live face-to-face time with students on a regular basis. If this not possible, however, then I suggest that you look for other ways to increase the speed of the feedback loop. Whatever you do, though, the feedback should be frequent, and it should be as personal as possible.

The third, and last, manifestation of the problem of online college that I want to address is the issue of workload. Interestingly, I have found that many professors new to online teaching tend to think either that the workload needs to be eased up or that it needs to be piled on. The approach of easing up seems to be based on the (correct) theory that it is harder to learn in the online environment, and the approach of piling on seems to be based on the (also correct) theory that students have more free time when they don’t have to attend regular class meetings. My view, however, is that both of these approaches diminish the feeling of the college experience. On the one hand, the “easing up” approach sends a message like “this is not really college, so let’s just take it easy,” and, on the other hand, the “piling on” approach sends a message like “this is not really college, so you’re all on your own.” My view is that the workload should be more or less the same as it is in a campus classroom. Whatever the workload looks like in your campus classroom, I would suggest that you keep it at about that same place: don’t ease up, but don’t pile on either. Set the bar at a college level.

I hope that these remarks are at least somewhat useful. If any of you need any support, advice, or just a shoulder to cry on, please don’t hesitate to reach out. I’m happy to help any way that I can. Good luck to all of us!

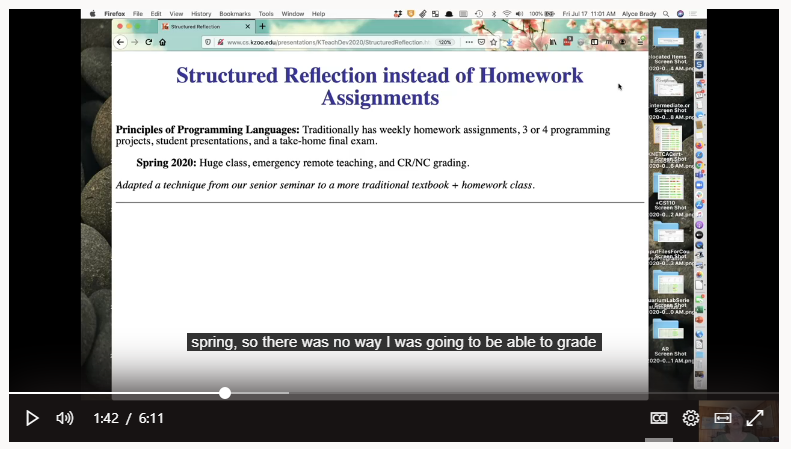

Ideas for Low Stakes, High Engagement Assignments — Alyce Brady

For several years I’ve been interested in shifting my grading practices to focus more on learning than on the kind of content knowledge that frequently rewards prior knowledge and privilege. The move to CR/NC grading in Spring 2020 gave me an opportunity to experiment with this further. The key concern that I and many other K colleagues had, though, was whether a CR/NC grading system would lead to less motivation and less engagement among students.

My experience this spring convinced me that lower stakes grading does not have to lead to lower levels of student engagement. In fact, two experiments were so successful that my CS colleagues and I plan to continue these approaches across many of our classes, whether remote or in-person, and whether CR/NC or letter-graded.

The first 6 minute video talks about turning rubrics that awarded points for required criteria into ones that awarded checkmarks, dramatically reducing the number of points per assignment. This approach is essentially a very mild form of gamification. (It is also somewhat similar to specifications grading.)

The second, 6 minute video discusses a move to replace traditional homework assignments with structured reflection assignments. My original motivation was to reduce grading time, since the class was significantly over-enrolled. I feared that some content learning would be lost, but found that the weekly writings encouraged students to develop and articulate greater depth and integration than the older homework assignments.

This video is posted at Stream. Click here to learn more about Stream.

Goodbye Emails, Hello Teams Chat — Nayda Collazo-Llorens

The Chat option in Microsoft Teams turned out to be an effective way to communicate with students, to the point that we decided to use it instead of email communication.

It offered casual and immediate exchanges (many of us installed Teams on our phones) and I would usually reply right away. It was convenient for students in both my Basic Drawing and Digital Art classes to reach out to me, or to the rest of the class in the group chat we set up early on, with questions as they worked on their projects.

Drawing students could send pictures of their in-progress drawings for feedback. Digital Art students were able to ask questions which would often lead to an impromptu video chat in order to share their screens with me.

It allowed me to see what they were working on and either help with technical issues or offer feedback. I found Teams Chat to be efficient and timesaving, but most importantly I felt it was the closest thing to being together in a studio classroom where I am there to answer questions and help students as they worked on their projects. It was also a quick and easy-to-use tool for me to reach out to students and was surprised by their prompt replies.

Both courses were taught asynchronously and incorporated different platforms. Moodle served as the main repository of information while Padlet served as an interactive collective space (see Sarah Lindley’s post). We also held optional Zoom meetings every week and I found that reminding students of the meeting through a chat message a few minutes prior offered good results.

COVID-19 Spring – It turns out some of my choices align with recommended practices! — Jeff Bartz

After a week of doomsday scrolling in March 2020, it was time to get to work. But what work? The technology options, activity alternatives, and advice for virtual classes were overwhelming. I made some choices and they ended up aligning well with a list of recommended practices published in July 2020:

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES FOR ONLINE INSTRUCTION from Means, B.; Neisler, J. Suddenly Online: A National Survey of Undergraduates During the COVID-19 Pandemic; Digital Promise: San Mateo, CA, 2020.

- Assignments that ask students to express what they have learned and what they still need to learn

- Breaking up class activities into shorter pieces than in an in-person course

- Frequent quizzes or other assessments

- Live sessions in which students can ask questions and participate in discussions

- Meeting in “breakout groups” during a live class

- Personal messages to individual students about how they are doing in the course or to make sure they can access course materials

- Using real world examples to illustrate course content

- Work on group projects separately from the course meetings

Without knowing that I was doing it, my class was constructed using aspects of Design Thinking. Our class had five major themes – Energy, Efficiency, Fuels, Climate Change, and the Ozone Hole – I thought the major themes would keep the students (and the instructor) interested. Assignments and activities were geared toward understanding the major themes using the standard physical chemistry that we have done at Kalamazoo College for decades.

Our class had asynchronous components aligned with the MWF schedule, with online assignments due each day. Some of the asynchronous activities in Spring 2020 were the same as if we would have met in-person: recorded flipped lectures linked on Moodle, targeted textbook reading, Moodle quizzes on the flipped lectures, Moodle quizzes on the targeted reading, and electronic homework. Students did one assignment looking at aspects of energy they thought would be interesting for the professor to learn. I collected laboratory data and asked the students to analyze it in the same way we would have done in-person.

The synchronous components were weekly problem solving sessions over Zoom. The students showed up, did a warm-up activity, solved problems in breakout rooms, then came back for a closing activity.

Here is how I implemented the recommended practices for online instruction:

| Practice | Implementation | Needs Work |

| 1. Reflection on Learning | ✓ | |

| 2. Breaking up class activities |

|

|

| 3. Frequent Quizzes |

|

Add more embedded questions |

| 4. Live sessions |

Figure out when to hold sessions

|

|

| 5. Breakout rooms during class |

|

When I popped into some breakout rooms all the microphones where muted. I need to assign roles to the groups and have somebody report out the results from the group. A helpful resource for groupwork |

| 6. Personal messages | With lots of online work, professor can see each student’s progress. Students who were falling behind got messages either email or instant messages through Remind or Slack. More students chose Remind than Slack. |

|

| 7. Real-world examples | Created a pre-class movie trailer to describe the applications using iMovie that was sent to all of the students. Putting out the applications that we would study made it important to work them into the class. | |

| 8. Group projects | Students chose whether they wanted to work in laboratory groups. |

Should we do more group work?

Pros: Cons: |

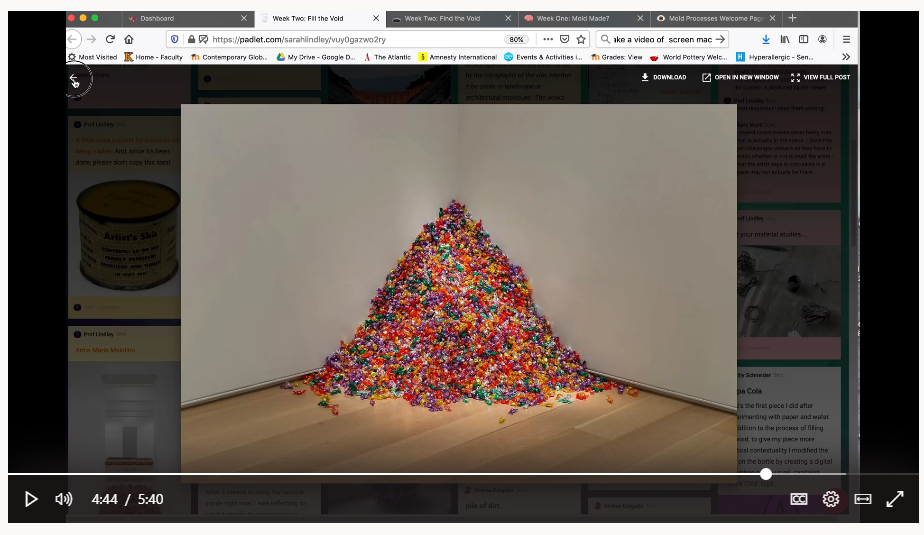

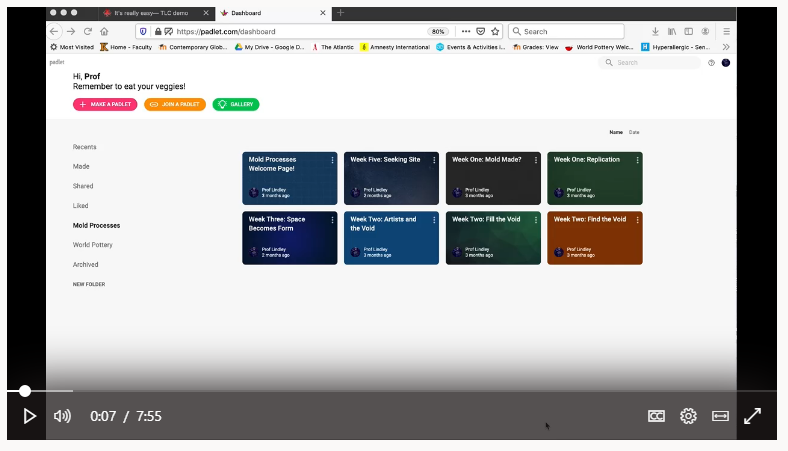

Online Shared Workspace Environment with Padlet — Sarah Lindley

Lots of people wonder how it would be possible to teach ceramics and sculpture online. It turns out that giving up the messy materials of clay and plaster was less disruptive than losing the group discussion and shared workspace that are essential to a sense of community and rapid artistic growth. This 5-minute video shows how I used the interactive platform of Padlet to introduce assignments, emulate a shared workspace environment, and foster asynchronous discussion. Padlet is colorful, easy to use and edit, and encourages creativity. It’s also nonlinear (unless you want it to be), and nonhierarchical. I used my own $10/month account to create all the Padlets, which meant students were able to use a free account for the entire term.

Watch this 8-minute “how to” video to see how easy it is to start using Padlet and visit the Padlet from the video to see how it works.

These videos are posted at Stream. Click here to learn more.

I don’t like the ads and lack of security with Youtube, so I tried using Vimeo for streaming videos at the beginning of the term. After some consultation with the Amazing Josh Moon, I realized that Streams was easier and better than Youtube, because

- videos can be linked directly to Team sites and/or you can even create a closed video channel for your class

- you can create the video so it is available to the entire college community, just your class, or just a few people

- you can see how many times the video has been viewed

- Streams automatically develops text captions for the narrative

- no ads

- no subscription fee

Alternatively, I also found OneDrive to be very useful for short videos. OneDrive tells you WHO watched the video. That was helpful for having keeping track of engagement.

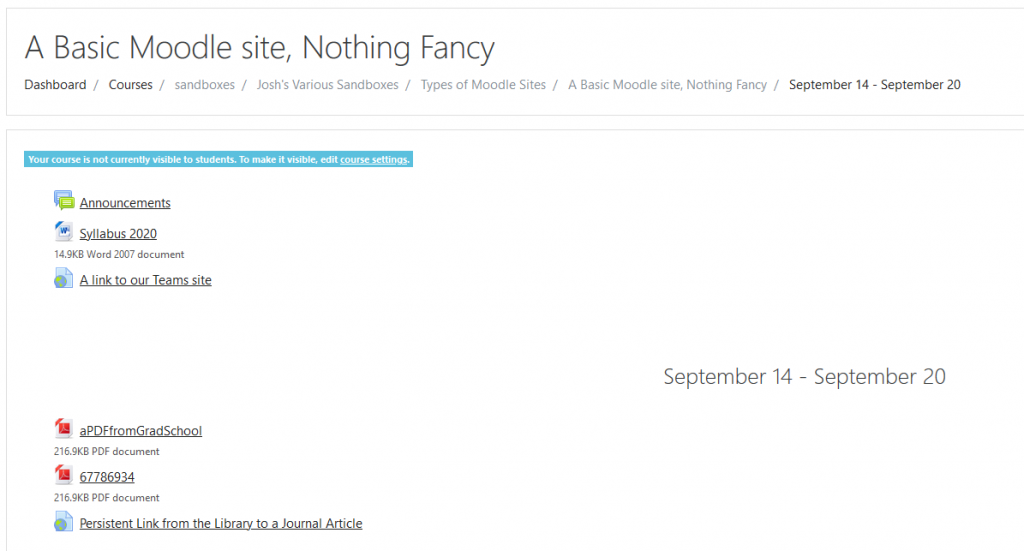

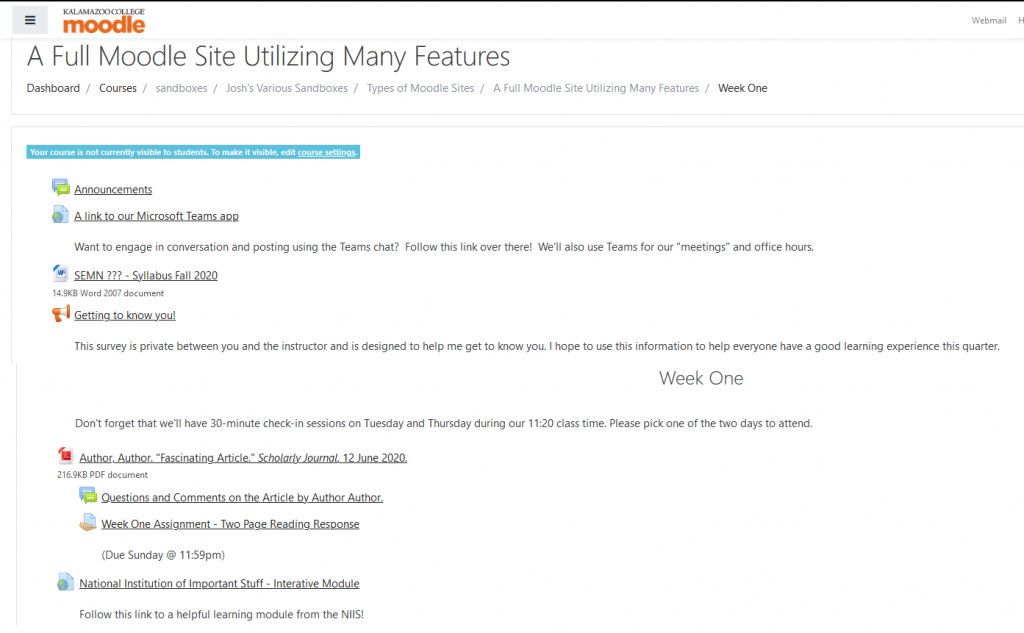

Four Models for Your Moodle Course — Josh Moon

Using Moodle does not mean that there is one solution for every instructor, group of students, discipline, or pedagogy. With this in mind, we’ve created four different models to demonstrate what various utilizations of Moodle by an instructor might look like:

- The Basics: A very simple, minimalist Moodle example

- A full-featured example using many features

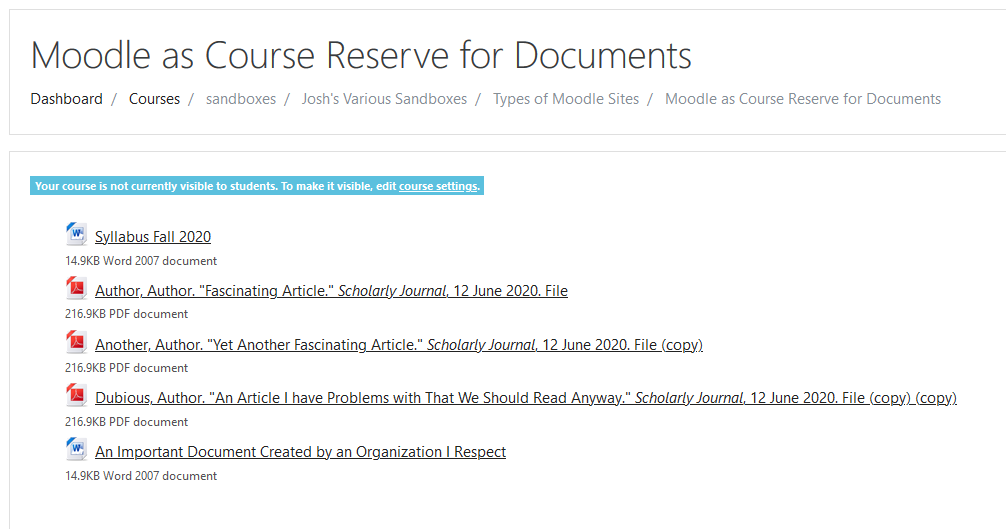

- The Course Reserve: An example of a Moodle site that serves mostly as a course reserve of readings

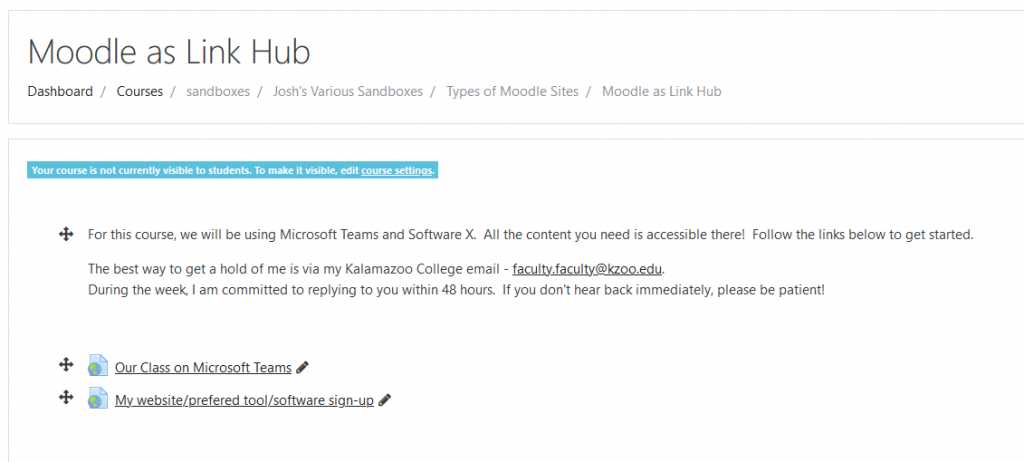

- The Link Hub: An example of a Moodle site that merely provides links to other sites (e.g., Teams site)

There are other options imaginable, so adjust these to meet your needs.

The Basics

This is quickest, simplest approach using the default course format. The instructor here has dragged-and-dropped their readings and other files directly from their computer (note: this brings along the file names but you can clean that up). They’ve done the same with the syllabus and added a few links with the URL tool. There are no explanatory text or instructions, no Assignment dropboxes, but that’s okay. This is the basics to provide students with the syllabus and readings.

A Full Moodle Site Utilizing Many Features

My “How to Organize a Week of Online Learning in Moodle” post from spring is based on this model. While this uses a similar weekly structure to The Basics site, you’ll see important differences. In terms of formatting, the instructor has used the Description fields to offer explanatory text about activities. File names have also been cleaned up and renamed (full citations are a copyright recommendation). They have added more tools including a discussion Forum, Assignment dropbox, and a Feedback survey. Some resources utilize “Move Right” to imply their direct relationship to the reading PDF and provide structure. Again, there are many gradients between this option and the Basics. It’s all about the features you and students could benefit from.

The “Course Reserve.”

This Moodle site has done away with the weekly format and placed all content in a list at the General (top) section. The idea here is to replicate a course reserve and supply students with the reading documents that they need for the quarter. If you already have a plan to facilitate discussion, support collaboration, receive assignments, and just need a convenient space to supply students with documents, this is the template for you.

The Link Hub

If you’re doing all of your digital communication with students on another platform or with other software, you can keep Moodle to a jumping off point with links. Even if you’re not spending much (or any!) time on Moodle, the goal here is to help students stay organized and have at least one, consistent hub to keep their online course content accessible that every instructor is using in some capacity.

Taming the “Brute Force” Approach to Create a More Sustainable Online Course — Patrik Hultberg

Brute force: the application of effort of force instead of efficient, carefully planned and precisely directed methods. That sums up my approach to the sudden switch to remote teaching and learning. As it turns out, it can work. But 10 weeks of constant around the clock teaching and decision-making had taken its toll. Over the last few weeks I’ve tried to dissect my courses in an effort to determine what techniques were helpful and perhaps what I should change for the fall. My goal is to ensure that my next experience teaching a course with an online backbone is efficient, carefully planned, and hence less work.

I have the following goals:

- Set limits on my own availability

- Make some assessment activities automatic

- Use technology for more efficient feedback to students: audio, video, annotation

- Encourage group work

- Implement low-stakes assessment related to my lecture videos

- Some form of conditional access in Moodle

- Microsoft Teams for student group discussions

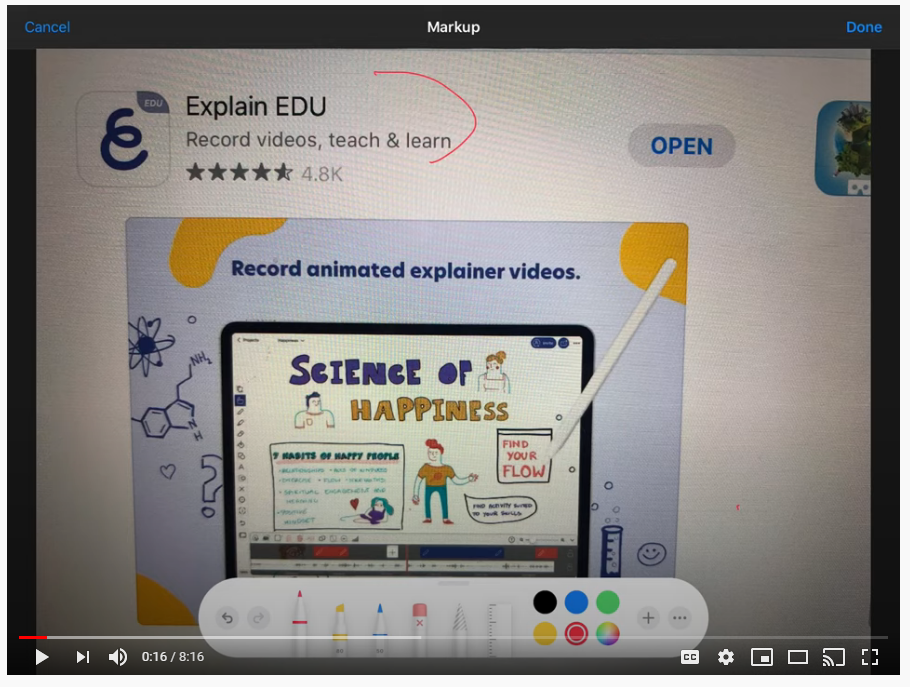

Explain Edu: An iPad App for Recording Powerpoint Lectures — Ann Fraser

In this video, Ann walks us from beginning to end of the process of using a program called Explain EDU to record lectures . It works on iPhone and iPad. You can import pdf files of your PowerPoint lectures — one slide per page — and then narrate the slides. You can do the narration slide by slide, avoiding having to make one continuous recording. It allows you to draw on the slides as you narrate.