After attending Dr. Amer Ahmed’s faculty workshops on Intercultural Skills and Inclusive Pedagogy, I have become more aware of how the teacher is traditionally positioned as the “knower”, and students are expected to give as “perfect” as possible a “performance” of knowledge dispensed by professors and textbooks.

And I began to think about how our classrooms don’t always provide a space for not knowing – especially when our Class Calendar says it’s time for a Test or Term Paper, dictating when students are expected to “show how much you know.”

This is a simple exercise I added to the Midterm Discussion Exam for my Developmental Psychology course in Fall 2020 and am currently implementing again for two sections in Winter 2021. I didn’t administer the standard Blue-Book Essay Midterm as I had for 20+ years, as I wanted to find alternatives to written exams during online courses. This simple exercise assesses not only what students know, but what they do not understand yet (“fuzzy areas”) while taking a Test. (This was incorporated into a Discussion-style test but could be adapted for Written Tests and Papers).

Here’s how we did it:

- I didn’t reveal to the students ahead of time that I was going to do something different. I gave them a Mid-quarter Study Guide, and simply wanted them to review and prepare the course material as best as they could.

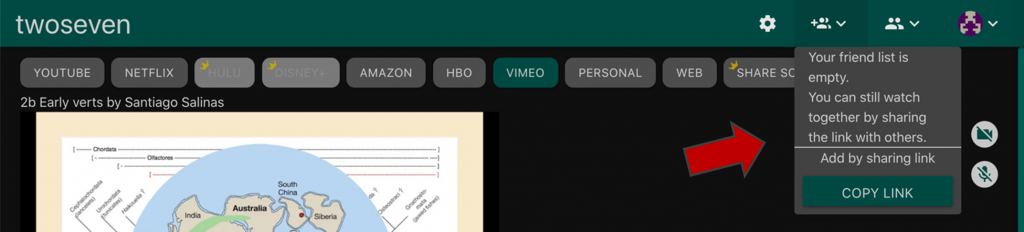

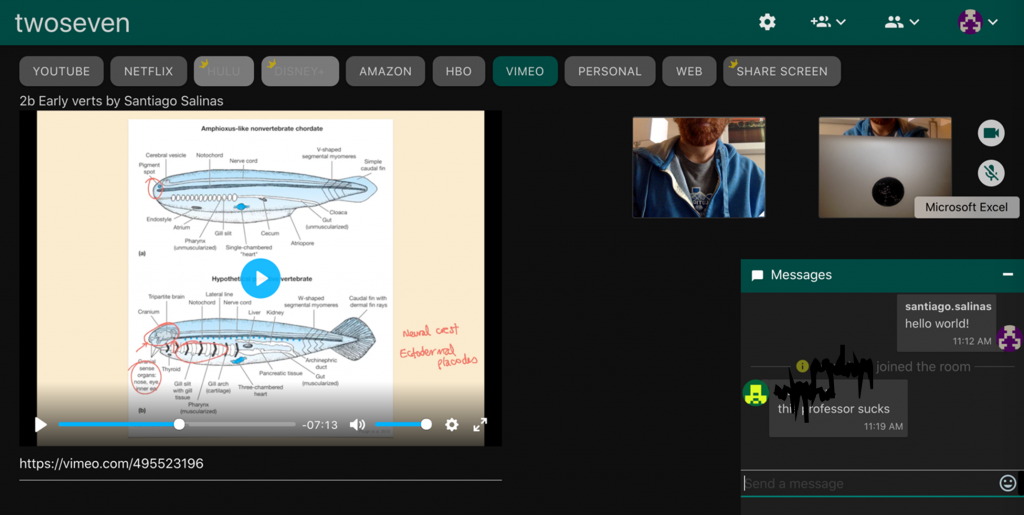

- I divided my class of 24 into four groups of 6 students. I met with each group for 100 minutes, with a 5-minute “stretch break”. (This took almost 7 half hours over the course of three days, but I didn’t hold synchronous classes that week).

- Toward the beginning of the discussion, I asked each student to identify their favorite topic in our class so far, give examples of why it was intriguing – and then identify what was the “fuzziest area” about that topic? (I tried to “normalize” having fuzzy areas, by saying something like “… because no matter how well we understand a topic, there’s always going to be something that’s a little murky or fuzzy, and not as clear as the rest”).

I didn’t know how it would go. Would they claim everything was pretty clear already? Would they be reluctant to reveal what they didn’t know during a Discussion Test? And how would this translate in an online situation, via MS Teams?

To my surprise, students were quick to point out “fuzzy areas” – especially after they had just had an opportunity to talk about their favorite topic, often with great enthusiasm and gusto.

- In our small groups of six, I usually started with a student who seems comfortable talking in class, to set the tone. After the student identified a “fuzzy area,” I would empathize first, then probe: “Oh yes, I see others nodding. I remember needing more time to grasp that one. What about Bronfenbrenner’s ‘mesosystem’ is most fuzzy or confusing?”

“Well, I understand the definition is the linkages between microsystems, but it’s hard to totally see how it works.”

“Okay, let’s get some group help – and then I’ll clarify as well as I can. What about Robin’s question: Can anyone give an example that would illuminate this level of the model?”

- Note: I didn’t do the “group help” step the first time. Out of habit, I jumped straight from the student’s question to giving an explanation (and then invited add-ons from peers). I played “dispenser of knowledge” too soon and took some of the joy of collaborative discovery away.

Adding this step allowed peers to scaffold each other (in their own language and with their own kinds of explanations) before I entered to summarize, clarify, and probe further. That way, students frequently credited peers for breakthroughs (“the example Megan gave really helped me get the concept”).

Another nice outcome of sharing “what I don’t yet know” in a group: some students later said it helped them realize that they weren’t the only ones that hadn’t grasped something – especially when they heard more confident students talk about “fuzzy areas.” This could be especially helpful for our first-generation college students, students of color, and students with special challenges; when not knowing is not kept a secret, it may help alleviate the loneliness of assuming you’re the only one that “didn’t get it”.

- Structure/Time management: I first posted all 6 students’ “fuzzy areas” to quickly plan a structure for our discussion — by grouping overlapping questions together, and deciding on a logical order to tackle them. I tried my best to include all students’ questions, folding in more tangential points into core concepts. This method made the best use of our time.

On most topics, students contributed helpful points to fill in the gaps, and there were some neat breakthroughs in each group. At the end of each round, I tried to provide a clear summary or synthesis (“So to sum up, we can understand the mesosystem as representing…”). When it came to me, I would add something new, with the hopes of continuing to teach and maybe even lead to another “aha” moment together. Often at the point of group discovery, there is a special readiness for another shift in thinking.

- Although I implemented this simple exercise in Midterm Discussions, it could easily be adapted to Term Papers and (written) Tests. We might encourage students to fill in a box at the end of a paper or test where they can convey one or two “still fuzzy areas” or “what’s still coming together for me” (with a clear statement that this will not affect the grade). This can give us insight into what to review and reinforce in our next module.

I didn’t focus on “fuzzy areas” for the Final Discussion Exam, for which I targeted other learning goals. This was perfect for the Midterm, allowing me to fill in gaps and reinforce certain principles for the last month of the course. But many students spontaneously brought up “fuzzy areas” on their own during the Final (which we addressed together), having learned that our class was open to this!

The “take-aways”:

The “fuzzy areas” was only one portion of our group discussion, but when I asked students what they liked or learned most from our time together, most described a breakthrough from the “fuzzy areas” part. When I asked why this was helpful, many said it’s because it departs from the standard way we test – with an approach that seems intended to assess what they “know”, and “catch” what they did not study well, or did not fully grasp. As one student put it, “at that point it’s to judge it and not to teach it.”

Many times, when we introduce a new concept in class, and stop to invite questions, no hands go up. It is only later, as students are pulling together all the information to prepare for a test – or actually taking the test – that they see where their understanding is incomplete. If we provide a safe space, somewhere in our spoken or written tests and papers, to convey those “fuzzy areas” and address them, the test is not just the measure of one’s learning but a tool for further learning.

As one student put it:

“Sometimes I don’t know what I don’t know till I’m taking the test, and then it’s too late… I really liked this discussion test, because you asked us to talk about the fuzzy parts, so we could close the gaps.”

-Siu-Lan Tan